Spectrochemical Series

The spectrochemical series is a list of ligands arranged according to the strength of the crystal field they produce when bound to a metal ion. Different ligands affect the energy levels of a metal’s d-orbitals in different ways. This series is based on experimental observations, especially from the electronic absorption spectra of transition metal complexes. [1-4]

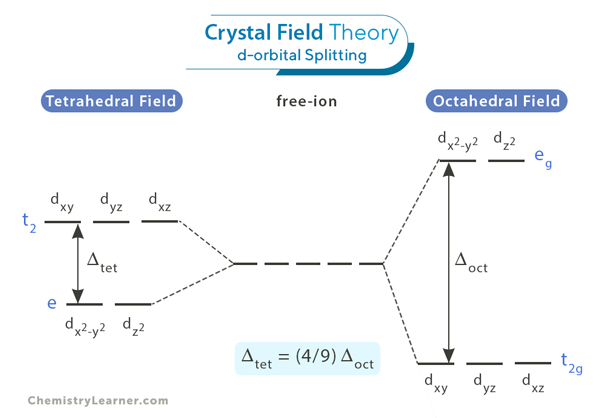

When a ligand binds to a metal, the metal’s d-orbitals split into two energy levels. Some ligands cause a large splitting of the d-orbitals (strong-field ligands), while others cause only a small splitting (weak-field ligands). The energy gap between these levels is called the crystal field splitting energy. By studying the wavelengths of light absorbed, scientists can estimate the size of this energy gap and determine the strength of the ligand field.

A commonly used form of the spectrochemical series is:

I⁻ < Br⁻ < SCN⁻ < Cl⁻ < F⁻ < OH⁻ < H2O < NH3 < en (ethylenediamine) < NO2⁻ < CN⁻ < CO

Interpreting the Spectrochemical Series

Understanding how ligands affect the metal ion they are attached to is key to interpreting the spectrochemical series. When ligands surround a transition metal ion, they interact with its d-orbitals, causing them to split into two distinct energy levels. The size of this energy gap (Δ) depends on the strength of the ligand. [1-5]

Weak-field ligands (e.g., I⁻ and Br⁻, on the left of the series) cause only a small splitting of the d-orbitals. Because the energy gap is small, electrons prefer to spread out among the orbitals – even if that means occupying higher energy levels. This results in high-spin complexes, which usually have more unpaired electrons and are often magnetic.

Strong-field ligands (e.g., CN⁻ and CO, on the right of the series) cause a large splitting of the d-orbitals. In this case, it is energetically more favorable for electrons to pair up in the lower-energy orbitals rather than occupy higher ones. It leads to low-spin complexes, which have fewer unpaired electrons and are typically less magnetic.

The position of a ligand in the series also depends on its donor atom – the atom that actually forms the bond with the metal. Ligands with highly electronegative donor atoms, or those capable of π-bonding (either donating or accepting π-electron density), tend to cause greater splitting of the d-orbitals. These π-donor or π-acceptor interactions significantly influence whether a ligand is weak- or strong-field.

Factors Affecting Ligand Field Strength

The strength of a ligand field, i.e., how much it can split the d-orbitals of a metal ion, depends on several factors: [1-5]

1. Nature of the Ligand

Ligands differ in how effectively they interact with the metal’s d-orbitals. Ligands with highly electronegative donor atoms (like F⁻) typically form weaker fields, while ligands that can participate in π-bonding (like CO or CN⁻) are generally strong-field ligands. The size and charge of the ligand also matter: larger, less tightly bound ligands like I⁻ create weaker fields, while small, strongly bound ligands like NH3 or CO create stronger ones.

2. Type of Metal Ion

The oxidation state and position of the metal in the periodic table affect the strength of the ligand field. Metals in higher oxidation states exert a stronger electrostatic pull on ligands, resulting in greater orbital splitting. Also, heavier transition metals (those in the second and third rows, such as Ru or Ir) typically show stronger crystal field effects than first-row transition metals like Fe or Co.

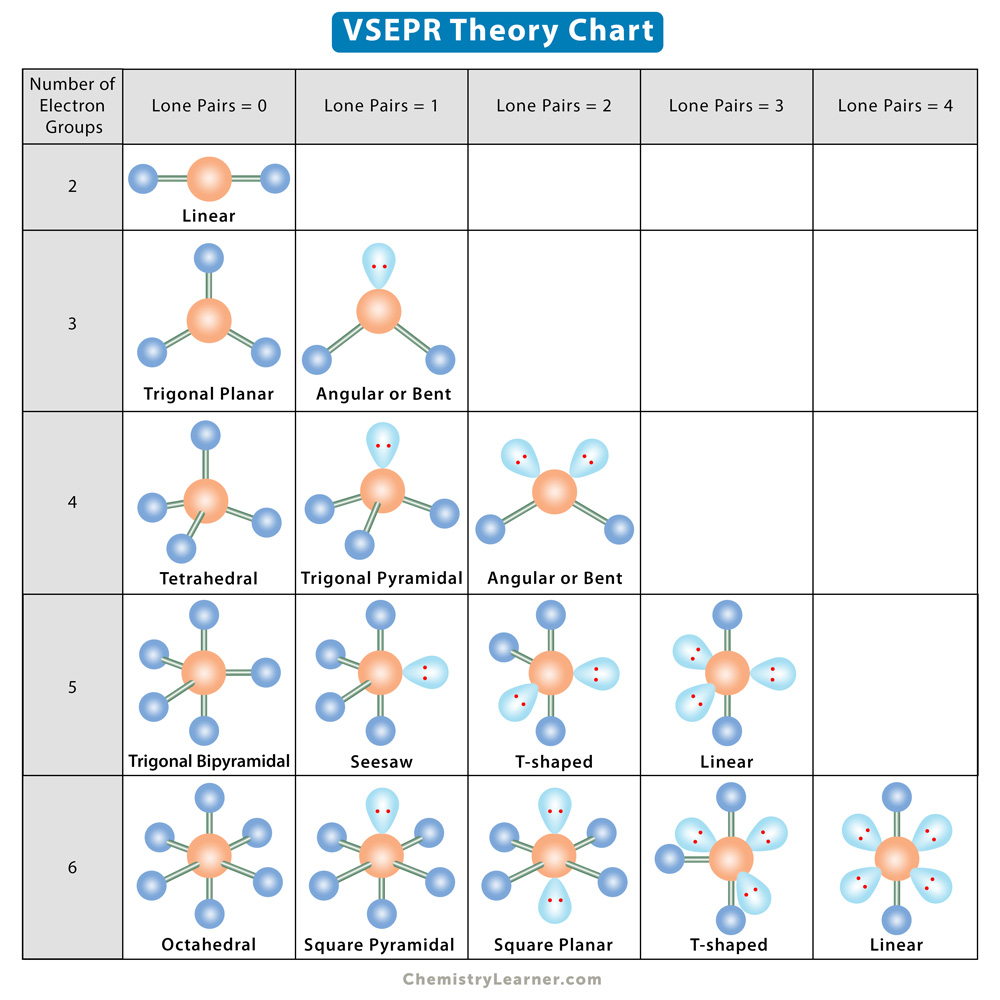

3. Geometry of the Complex

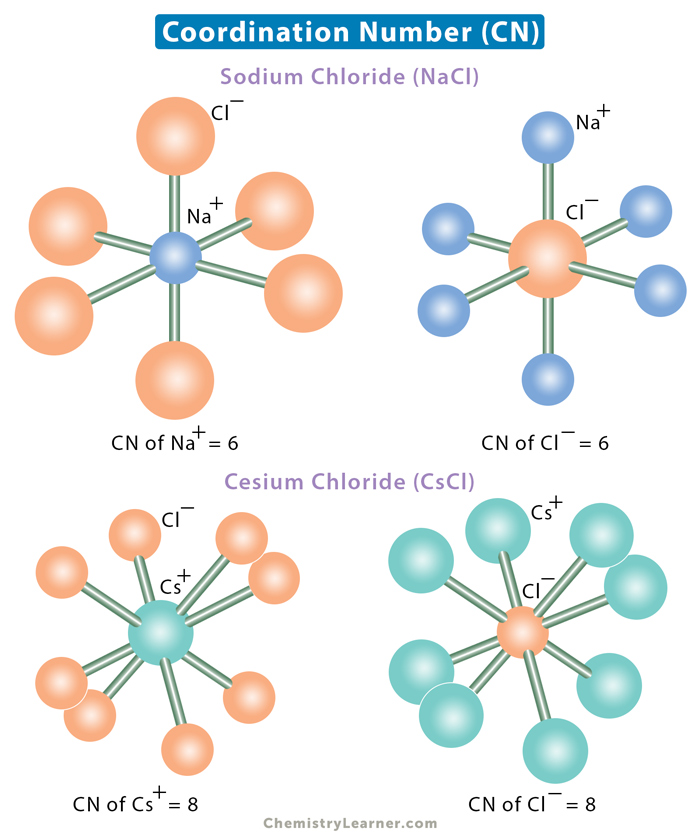

The geometry of the metal complex, whether octahedral, tetrahedral, or square planar, also influences orbital splitting. In octahedral complexes, ligands point directly at the d-orbitals, causing stronger repulsion and a larger energy gap than in tetrahedral complexes, where ligands approach between the d-orbitals. Square planar complexes (common for some d8 metals like Ni²⁺ or Pt²⁺) can exhibit even greater splitting than octahedral ones.

Applications of the Spectrochemical Series [1-4]

- Predicting electronic configuration: Helps determine whether a complex will be high-spin (more unpaired electrons) or low-spin (fewer unpaired electrons)

- Explaining the color of metal complexes: The amount of d-orbital splitting affects the wavelengths of light absorbed, explaining why some compounds appear blue, green, or red.

- Predicting magnetic behavior: Indicates whether a compound will be paramagnetic (with unpaired electrons) or diamagnetic (all electrons paired)

- Important in bioinorganic chemistry: Helps explain the function of ligands in biological systems like hemoglobin and cytochromes, where metal ions play key roles

- Useful in catalyst design: Guides chemists in selecting ligands that create an optimal environment around a metal center to enhance catalytic activity

- Guides ligand selection: Choosing appropriate ligands helps design materials with desired electronic or magnetic properties.